This post was originally published on The Establishment by Natasha Burge.

‘You have to be brave to make it in this industry.’

I’m rushing down the winding alleyways of Adliya, the Kingdom of Bahrain’s funkiest district, on my way to the album launch party for the island’s only homegrown baroque’n’roll band. It’s November, but the evening is warm and jasmine-scented. Groups of people wander streets crowded with cafes, shawarma stands, and bougainvillea-draped villas that look grandiose in the moonlight.

I’m halfway through a whirlwind 24-hour exploration of Bahrain’s dynamic art scene, as seen through the eyes of some of the country’s most talked about young, female creators. Bahrain is the smallest nation in the Middle East — you’ll need to squint at the map and look for the islands off the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia to find it — but its influence on history has been tremendous. As the heart of the ancient Dilmun civilization, Bahrain spent millennia as a trade hub, saturated by the ebb and flow of cultures, which left the nation with an eclectic feel unique in the Arabian Gulf.

The Gulf region has made waves in the art world recently, with Qatar building a collection of international masterpieces at such an impressive rate that it has become the world’s largest buyer of contemporary art, and Art Dubai and the Sharjah Biennial making the region a key stop on the international art fair circuit. In the midst of this, Bahrain marches to the beat of its own drummer by balancing an embrace of international arts culture with a celebration of homegrown creative talent — the latter of which has made the country an epicenter of a new art movement.

I began my exploration earlier that afternoon in the lobby of a plush hotel where I met with Sarah Nabil, the region’s first female hip-hop producer and composer. Sarah works with Outlaw Productions, a pioneering hip-hop label in the Middle East that’s behind hits like “Ee Laa” and “Samboosa.”

In contrast to the glitz of the lobby, Sarah was the epitome of effortless cool as she explained the nuances of what is still “a music scene, not yet an industry.” Sarah’s foray into music production started when she met her mentor DJ Outlaw at 17. She knew instantly this was the career for her. “At the time there were no other women doing this; there were no stepping stones for me as a woman in the industry.”

In the seven years Sarah has been with Outlaw Productions, she has seen the local music field evolve significantly. “It’s an exciting time because artists are trying new things and the public is starting to appreciate local talent more. People used to say that if you want to make it in music, you have to leave Bahrain. We want to change that. We want to build this industry from the ground up and in 30 years look back and say we were a part of that.”

Outlaw Productions is keen to nurture young talent, which makes Sarah’s work as the music curator at Malja, the region’s first community art hub, so important. Malja, which means “shelter” in Arabic, was launched by Red Bull in 2015 to provide a collaborative space for artists of all mediums. The space holds regular open mic nights, and Sarah teaches workshops in music production and song structure.

“Malja is the only place in Bahrain with a free recording studio,” Sarah says. “It’s an amazing resource that has encouraged artists to be braver, and you have to be brave to make it in this industry. Young girls have told me they find what I’m doing inspiring. That gives me a responsibility to continue.”

That evening I met another Malja collaborator, Ramah Al Husseini, at a café on the beach where we watched the twinkling lights of dhows bobbing on the distant horizon. After earning a degree in studio art in Canada, Ramah returned to Bahrain five years ago and spotted something missing. “There were no open call exhibitions. Everything revolved around the same galleries and the same people so it was tough for emerging artists. Malja played a part in changing that.”

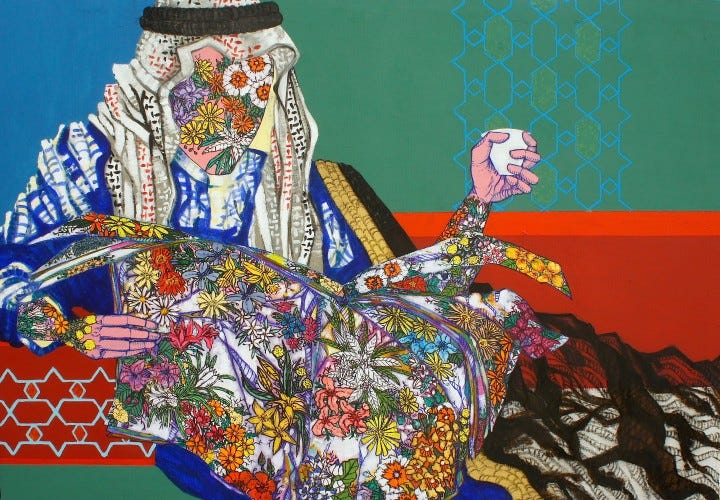

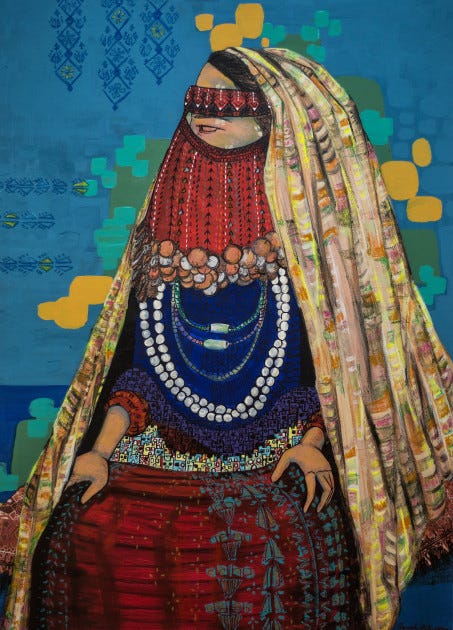

Tapped by the team behind Malja to be their art curator, Ramah quickly established herself as a linchpin of the art scene, curating exhibitions, teaching workshops, and cultivating fans of her dazzling paintings. At the core of her creative practice is a drive to reveal the connective tissue between ideas, which she says springs from her own background. She is a Saudi citizen of Palestinian descent, with family ties to Jordan and Dubai, who calls Bahrain home.

“When people ask where I’m from, I like to say that I’m Arab,” she says.” I’m not from a particular place; I’m from every place.”

Ramah echoed something I’ve heard expressed before by local artists: a desire to be viewed as individuals, rather than as symbols of an entire region. Stereotypes about the Middle East often mean regional artists find themselves viewed through a politicized lens on the international scene, which obscures their individuality and leads to one-note interpretations of their work. These nuanced considerations take center stage in Ramah’s pieces, which explore concepts of identity, culture, and tradition. “I don’t want to dictate to people what is right or wrong. I want to raise issues and ask questions.”

Ramah cited social media as one factor in the changing nature of the local art scene:

“Social media allows anyone to share their art; you don’t have to wait for a gallery or have the right connections. If you make something, you can post it. There used to be the belief that imported art had more cache but that is starting to change. First we need awareness, then appreciation, and then investment.”

After leaving Ramah, I jumped in a taxi and sped toward tonight’s Belly of Paris gig. The self-described “Anglo-Indo-Argentine-Palestinian-Hungarian” group is the epitome of the island’s au courant eclectic vibe. Their “doom-pop” sound is reminiscent of a louche, decrepit aristocrat, and tonight is the launch of their first album, Peste, as well as a send-off as they begin their first Middle Eastern tour.

Yasmin Sharabi, the band’s backing vocalist and keyboardist, greets me at the door of the packed venue. In addition to her role in Belly of Paris, Yasmin is also an artist and curator who has been a central force in the changing landscape of the local art scene. The opening band takes the stage as we find a place at the bar. With a soft-spoken brilliance, Yasmin dissects the challenges and opportunities faced by local artists.

“Art is ingrained in the culture of Bahrain,” she begins. “It’s an ideal place to lead the regional art scene because it’s open-minded but has the weight of history to draw upon. There’s always been a dialogue between cultures here, which shows in the creativity we are seeing now. As institutional support grows, artists will have greater resources and the scene will develop even more.”

Yasmin describes a series of exhibitions she co-curated with Frances Stafford, “Double Tap,” which explored how social media builds bridges between people and cultures. “Through social media, connections can be made between artists who would have never otherwise met. It’s fascinating to see what can come of that.”

This urge to make connections is a cornerstone of Yasmin’s artistic philosophy. She is one of those indefinable creative types who turn their life into an embodied expression of their art. “I think of life as my art. Bringing people together to create an artistic community, that is my work.”

Yasmin is summoned to the stage, where Belly of Paris launches into a performance that leaves the crowd hollering for more. As I watch the fans singing along, I get the sense that something utterly new is taking shape between the throaty chords and the clamor of drums. As Yasmin said, the local music scene is embryonic, but that makes it all the more exhilarating.

The next morning, I make my way to the Manama souq. A tumult of shops, restaurants, and people, this is the beating heart of Bahrain’s history as a trade hub. In the store windows, bright paint lists the wares in a variety of languages — Arabic, English, Hindi, Farsi, and sometimes German and Japanese.

From the moment I meet Frances Stafford at a coffee shop, she crackles with energy. “I’m not a fashion designer,” she insists, even though I’m meeting with her, in part, to discuss Black Anaar, the fashion line she is launching later this month. She sees herself as more of a curator, almost a producer, tugging together threads of fabric, design, and people, to bring her stunning creations to life.

Frances, an art history major, first came to know Bahrain as a curator and exhibition specialist. While on holiday in Paris, she missed her flight home to Vancouver, which led her, on a whim, to visit Bahrain. In one of those serendipitous bits of synchronicity that seem so abundant here, she instantly fell in love with the island and its “kaleidoscopic” blend of cultures. “I was blown away by the talent and creativity and I knew I wanted to stay. I was made to feel so welcome it immediately felt like home.”

As director of the Little India and Bab Market events, held by the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities (the former Ministry of Culture), to breathe life into the historic souq district, Frances was tasked with a huge role. “More than 20,000 people visited these events. We had pop-up art galleries, vendors, workshops, and dance and musical performances. We wanted to commemorate Bahrain’s long history as a cultural hub and encourage the exchange of ideas. These events marked a jumping-off point for the current surge of creativity we see now.”

Her fashion label Black Anaar is her love letter to Bahrain. Anaar is an Arabic girls’ name meaning “radiant,” and it also means pomegranate in Farsi, Urdu, and Hindi, in reference to Bahrain’s longstanding cultivation of the fruit. Frances, who now divides her time between Berlin and Bahrain — “Bahrain calls you back, you can never really leave it” — finds fabric in the souqs and works with local tailors to create exquisite unisex kaftans and robes, paying homage to the traditional designs of the Gulf. “I go on treasure hunts through the souq until I find a fabric that inspires me. I learn from the tailors, I learn from the way my friends and models wear the pieces, and Black Anaar’s vision is continually evolving.”

Frances is passionate about sharing Black Anaar with the world — when I admire the flowing cover up she is wearing, she plucks at the sleeve and asks if she should take it off so I can have it — in part to break down stereotypes about the region. “Bahrain is a magical place but because of the misperceptions a lot of the world has about the Middle East, that story doesn’t get told enough. Synthesis and the blending of cultures that are at the heart of Bahrain and fashion is a way of communicating that idea.”

In her time here, Frances has seen a seismic shift in the art scene:

“There have always been a lot of ‘bedroom artists’ in Bahrain, people with amazing talent but no venue for collaboration. Now people are expressing their individuality and exploring the differences between us rather than pretending they don’t exist. There is energy in the margins and something exciting is happening.”

After saying goodbye to Frances, I wander through the buzzing streets of the souq, past the shops selling halwa and karak chai, past mountains of Persian rugs and towers of gleaming samovars.

My frenetic journey through Bahrain’s creative scene has made it clear that a new homegrown artistic spirit is breathing life into time-honored customs and igniting something never before seen in Bahrain, or the Gulf region. This blossoming creative movement is sincere; it unabashedly wears its heart on its sleeve and it has utterly captured mine.

Like I keep hearing, there’s something magnetic about this place. There is, most definitely, magic on the horizon.

Commenti